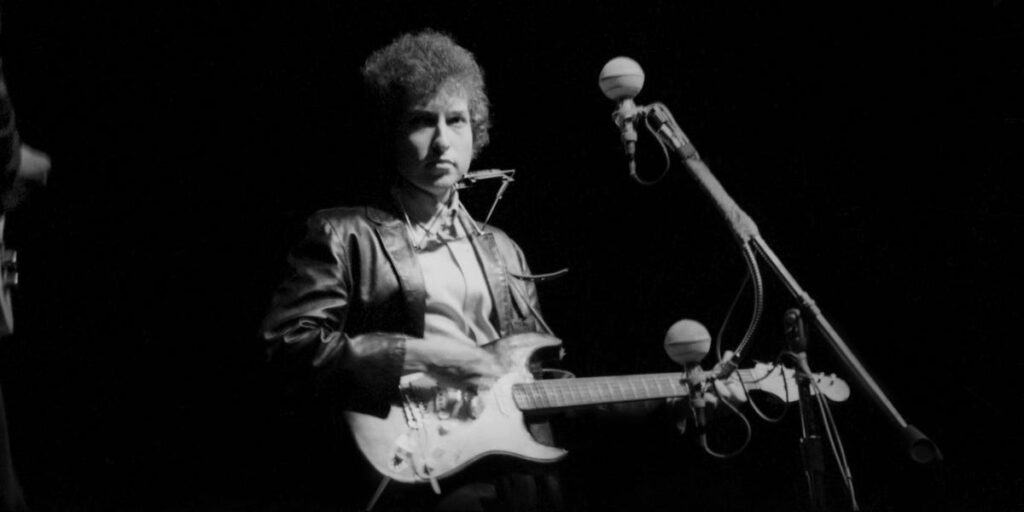

- “A Complete Unknown” stars Timothée Chalamet as Bob Dylan during his rise to fame in the ’60s.

- The movie’s climax is Dylan’s performance at the 1965 Newport Folk Festival.

- Dylan performed with an electric band, causing him to be ostracized from the folk scene.

James Mangold’s new film “A Complete Unknown” reaches its climax when Bob Dylan (Timothée Chalamet) takes the stage at the 1965 Newport Folk Festival, drawing boos from the crowd and disgust from his peers.

But out of all the performances Dylan gave in the ’60s, what made this one so controversial? To understand its outsize significance in Dylan’s career, as well as music history at large, it’s important first to rewind.

The Newport Folk Festival was cofounded in 1959 by jazz promoter George Wein and music manager Albert Grossman. (The latter is best known for representing Dylan between 1962 and 1970.)

Dylan made his debut at the annual event in 1963 alongside Joan Baez, a close collaborator who was already a folk superstar. He returned the following year for a solo set in his typically sparse style — guitar, harmonica, raw vocals — and sang now-beloved tracks like “Mr. Tambourine Man” and “Chimes of Freedom.”

Dylan amassed an adoring crowd in 1964 and became known as one of the festival’s biggest draws. He was expected to return for the 1965 edition, alongside friends and folk staples like Baez and Pete Seeger.

It was also expected that Dylan would deliver another solo acoustic performance. Instead, the 1965 Newport Folk Festival is better known as the night Dyan went electric.

‘An artist can’t be made to serve a theory’

The original script for “A Complete Unknown” was based on Elijah Wald’s 2015 book “Dylan Goes Electric! Newport, Seeger, Dylan, and the Night That Split the Sixties.”

Wald recounts how a 24-year-old Dylan took the stage with an electric guitar, breaking with convention and shocking — even enraging — the crowd who gathered to hear traditional finger-picked tunes.

Instead, Dylan opened with “Maggie’s Farm” (“Well, I try my best to be just like I am / But everybody wants you to be just like them / They say ‘Sing while you slave’ and I just get bored”) and “Like a Rolling Stone” (“When you got nothing, you got nothing to lose / You’re invisible now, you got no secrets to conceal”), backed by a full band.

Before the performance, Dylan had been growing agitated with the expectations placed on him by fans and the media, who were hailing him as the bastion of protest music. However, according to Baez, Dylan wasn’t particularly interested in politics beyond its service to his songwriting. His music leaned more toward commentary than activism.

“I think what happened with Bobby is the same as with The Beatles. They are really talented, but they don’t want to accept responsibility for what’s going on,” Baez said in 1967. “And the minute they write a song that was sort of saying, ‘I’m on this side or that,’ then everybody’s going to jump all over them for being part of a cause, and they don’t want it.”

At the time, the folk scene was all about social awareness and advocacy. Baez was a fixture at protests and civil rights marches, for example, while Seeger was avidly pro-worker and tracked by the FBI for suspected ties to communism. By contrast, Dylan avoided political events throughout the ’60s and even declined to denounce the Vietnam War, a cause that united many of his contemporaries. (When asked to do so by Sing Out! in 1968, he replied, “How do you know that I’m not, as you say, for the war?”)

Dylan’s girlfriend in the early ’60s, Suze Rotolo, said he balked at the idea of getting boxed in — as a person or a musician — in her 2008 memoir “A Freewheelin’ Time.”

“The old-left wanted to school him so he would understand well and continue on the road they had paved, the one that Woody Guthrie and Pete Seeger and others had traveled before him. They explained the way of the road and its borders,” she wrote. “Bob listened, absorbed, honored them, and then walked away. An artist can’t be made to serve a theory.”

In short, Dylan didn’t feel beholden to the folk tradition. So, on that pivotal day in Newport, he decided to swap his acoustic guitar for the famed Sunburst Fender Stratocaster.

“When Dylan took the stage with that unprecedented amped-in performance, he fatefully intertwined folk with rock ‘n’ roll,” Rolling Stone reported. “But more immediately, he was harassed by the audience, who booed him loudly and called him a traitor to the folk genre.”

The dissenters included Seeger, who had supported Dylan’s career since they met years prior in Greenwich Village. Seeger was also a prominent member of the festival’s board of directors and has been credited with booking Dylan for the lineup.

It’s been widely reported that Seeger, watching Dylan’s performance from the wings, told the audio technicians he wanted to chop the cables with an ax. (It’s unlikely that Seeger actually tried to cut Dylan’s sound, as he’s depicted attempting in “A Complete Unknown,” but rumors about that day can be hard to separate from reality. Seeger later said he was only upset because the sound was distorted.)

Not everyone was horrified. Johnny Cash was famously supportive of his friend’s shift toward rock, while Baez later told Rolling Stone, “I just thought he was very brave to do it, even though I didn’t like the sound of it. But I learned to like it, because he was still writing wonderful stuff.”

Still, Dylan was shouted off the stage in Newport after just three songs. After a brief intermission, he returned with his acoustic guitar to play “Mr. Tambourine Man” and, fittingly, “It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue.” The crowd cheered for these songs, but bootleg videos show Dylan looking stoic.

‘Judas!’

In the following years, Dylan was ostracized from the folk community. Fans thought electric Dylan was an out-of-touch sell-out, less authentic than acoustic Dylan, and they weren’t afraid to let him know.

“A Complete Unknown” shows a furious concertgoer screaming “Judas!” at Dylan in Newport, which actually did happen — only it happened several months later in Manchester, England, during Dylan’s 1966 world tour. (He’d just released “Blonde on Blonde,” which has since been vindicated by fans and critics as one of his best albums.)

One fan identified as Lonnie, who attended the Manchester show in question, is quoted in C.P. Lee’s 1998 biography “Bob Dylan: Like the Night.”

Lonnie told Lee he doesn’t regret how the crowd treated their one-time hero: “It was like, as if, everything that we held dear had been betrayed,” he said, adding, “We made him and he betrayed the cause.”

Ironically, the immediate backlash seemed to reinforce the very reason Dylan stepped back from folk music in the first place.

In his 2004 memoir, “Chronicles: Volume One,” Dylan said his admirers had been acting increasingly possessive. “Screw that,” he wrote. “As far as I knew, I didn’t belong to anybody then or now.”

Dylan’s rebellious streak made him perfectly suited for the rock world, which embraced him with open arms.

Dylan refused to play at the Newport Folk Festival for another 37 years before he finally returned in 2002. By that time, change and genre-hopping had become not a sticking point for Dylan’s fans but a key part of his allure.

Once again, he sang “Like a Rolling Stone.” This time, it was met with applause.

Read the full article here