- Russia is experiencing repeated struggles with its new ICBM.

- Russia used to use Ukrainian expertise to work on that type of missile.

- But Russia’s attack on Ukraine in 2014 and its 2022 invasion isolated it from that expertise.

Russia’s ICBM program is in trouble, facing persistent struggles with its new Sarmat missile. And it doesn’t help that it’s cut off expertise it once depended on by waging war on its neighbor.

“Historically, a lot of the ICBM manufacturing plants and personnel were based in Ukraine,” Timothy Wright, a missile expert at the International Institute for Strategic Studies, told BI.

Ukrainian expertise

Ukraine became independent when the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, but its defense industry continued to be intertwined with Russia. Ukraine has expertise in nuclear and missile technology, as well as manufacturing knowledge.

Russia had been decreasing its reliance but had not yet severed critical ties when it attacked Ukraine in 2014, leaving it with gaps that could affect development projects.

Since the dissolution of the Soviet Union, Russia has developed capable solid-fueled ICBMs. But with Sarmat, it decided to use a liquid-fueled system.

The problem with that “is that the Russians haven’t done this in about 30-plus years,” Wright explained. “They haven’t got any recent experience doing this sort of stuff with land-based ICBMs.”

Fabian Hoffman, a missile expert at the Oslo Nuclear Project, told BI that it’s “a bit of a question of: ‘Have they retained the expertise?’ Because all the people who built their previous missile have retired or dead.”

“Some of them are in Ukraine, which had a big part in the Russian ICBM program,” he said. “So that’s a major issue.”

Wright described Russia’s choice to use liquid fuel technology as “a really weird choice that they made” as it “is something the Ukrainians previously did for them.” He said “that’s one of the reasons why they’re having lots of problems.”

The Sarmat is designed to replace the Soviet-era R-36, which NATO calls the SS-18 “Satan.” Its earliest version first entered service in the 1970s and has been modified since.

The company that designed and maintained it, Pivdenmash, known as Yuzhmash in Russia, was in what is now modern-day Ukraine. (Russia appeared to target the Pivdenmash plant in an attack with a new missile type in November).

Ukraine cut ties

Russia wanted to develop more of this kind of expertise and capability itself. “After the dissolution of the Soviet Union, Russia found itself in a position where essentially it was having to rely on external countries to maintain its existing forces and also then contribute to the development of other ones,” Wright said.

But doing so was a challenge that took time. “So they continued working with Ukrainians up until 2014,” he said.

In March 2014, Russia annexed Ukraine’s Crimea region, claiming it as part of Russia despite international outcry, and ignited conflict in Ukraine’s east that continued until Russia launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022.

In response to Russia’s actions in Crimea, “the Ukrainians pretty much terminated all contracts around the maintenance of ICBMs at that point. So that’s where the big cutoff happens,” Wright said.

The collapse in cooperation between Ukraine and Russia “accelerated” Russia’s efforts to replace the R-36 so it would not rely on Ukraine as much, Maxim Starchak, an expert on Russian nuclear policy and weaponry, wrote in a 2023 analysis.

“All cooperation with Ukrainian contractors ceased,” and the responsibility for maintaining the R-36s went to Russia’s Makeyev Rocket Design Bureau. “But this was a stopgap solution. Launches ceased, with missiles and warheads simply undergoing annual checks.”

Ukraine banned military cooperation with Russia and stopped supplying Russia with any military components in June 2014. That left Russia without much of the expertise it wanted for Sarmat.

Neither of the two strategic-missile developers in Russia — the Makeyev Rocket Design Bureau nor the Moscow Institute for Thermal Technology — have recent experience developing a liquid-fueles ICBM, Wright said.

Ukraine also made other ICBM components, like guidance systems and security protocols to prevent the unauthorized detonation of a nuclear device.

Russian military experts had predicted Ukraine pulling its cooperation with Russia would completely collapse Ukraine’s defense industry. And while it did suffer, that industry is now thriving, with homegrown defense companies and major Western manufacturers all working in the country in response to Russia’s invasion.

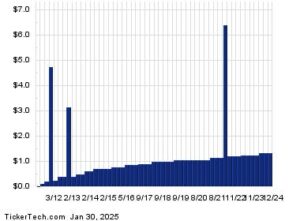

Russia still has many missiles that are hitting Ukraine and pose a big threat to Europe, and it has recently ramped up its missile production. But Russia’s aggressive actions in Ukraine appear to have continued to harm its missile program. Roscosmos, a Russian space agency that also makes missiles, said last year that canceled international contracts had cost it almost $2.1 billion.

Many countries have put sanctions on Russia in response to the invasion, and the sustained military effort is also hammering Russia’s economy. Hoffmann described Russia as having “really restricted monetary means” to fix its missile problems.

Sarmat’s problems

Russia’s RS-28 Sarmat ICBM appeared to have suffered a catastrophic failure during a September test, appearing to have blown up. Satellite pictures showed a massive crater around the launchpad at the Plesetsk Cosmodrome, a spaceport in northwestern Russia.

That apparent failure followed what missile experts said were multiple other problems. The powerful missile’s ejection tests and its flight testing have both been repeatedly delayed, and it previously had at least two canceled flight tests and at least one other flight test failure, according to the Royal United Services Institute think tank in London.

Russia has poured a lot of money and propaganda into the Sarmat missiles. President Vladimir Putin in 2018 bragged that “missile defense systems are useless against them, absolutely pointless” and that “no other country has developed anything like this.”

But it doesn’t work right. With the setbacks facing the Sarmat and no other replacement, the R-36 keeps having its life extended. Wright said that the missile is “already really, really past its service life.” And sooner or later, things are going to fall apart.

And Sarmat’s struggle “obviously is proof of the fact that whatever expertise there is in Russia right now, it’s not enough to complete this program in a satisfactory way,” Hoffmann said.

Read the full article here