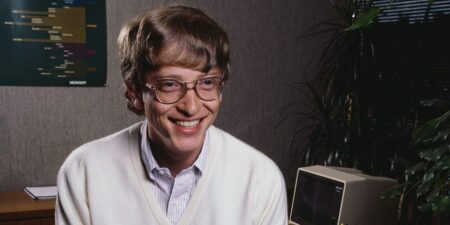

- When Judd Antin quit his job at Airbnb in 2022, he planned to switch careers.

- The transition was harder than he expected now that his time was his own and he’d no metrics to hit.

- Antin said teaching became an “anchor” that helped him find structure after leaving Big Tech.

Two years ago, after almost 15 years in tech, I left my job as head of design studio at Airbnb in search of something new. It didn’t go quite as I’d planned.

My tech career began in 2006 when I co-founded an ill-fated startup. After finishing a Ph.D. at UC Berkeley in 2010, I joined Yahoo and then moved to Meta, then known as Facebook, as a UX researcher in 2012.

I joined Meta at a time of immense growth and worked on projects like the shift to mobile, the first feed ads, and integrating news into Facebook.

After three years, in 2015, I moved to Airbnb as head of research. During my almost eight years there, I had a variety of executive roles in research, design, and product. I worked directly with the C-suite on top-level projects. I couldn’t have asked for more.

But burnout was in the rearview mirror, gaining on me. The guard was changing at Airbnb as a new generation of executives arrived. Many of us have had colleagues who’ve hung on at a company too long and become cynical despite their best intentions. I sensed it coming for me, and desperately didn’t want to be that guy. So I jumped ship in 2022.

I thought I’d feel relieved about leaving, and I do. But I’ve also struggled with a harsh realization: The tech industry had defined a core part of me. Leaving Big Tech forced me to re-evaluate what it means to be satisfied, productive, and useful. It’s been harder than I imagined.

Leaving Big Tech meant I had to rewire my approach to satisfaction

When I left Airbnb, I hoped to consult and teach, but I didn’t have a concrete plan. For the first few months, I lived off savings and my wife’s income before diving into new areas of work.

Soon after I left, I began to realize how much the industry’s expectations impacted my sense of satisfaction.

Those expectations started with my time — how I should work and how much I should work. I’ve never worked for Elon Musk as part of his “hardcore” work culture, but Meta and Airbnb were both intense and fast-paced.

Airbnb was particularly chaotic. I worked long hours and my calendar was stacked with meetings — but it was last-minute changes, ever-shifting priorities, and constant firefighting that really took a toll. Tech trained me to believe that the work is never done and my shift is never over.

Tech’s definitions of success also got their claws into me. We drive metrics, crush OKRs, and launch on time at all costs. If we can’t measure it, then it didn’t happen. As employees, we’re asked to judge ourselves and our worth by these measures.

And when I left my job, it all changed overnight.

I struggled to reconstruct my sense of satisfaction without the usual signals. My hours were my own. There were no meetings I didn’t want to take and no goals except the ones I set for myself.

At first, I was surprised that my empty calendar left me with more anxiety than freedom.

I thought I’d be able to detach from the “always-on” work culture, but years of training made it hard to put down my phone. I made personal lists and goals to replicate the feeling of success that business metrics had given me, but I often found myself feeling unproductive and unsatisfied nonetheless.

In retrospect, it’s obvious the industry’s expectations were unhealthy for me. It wasn’t just the stress and anxiety of a high-pressure career, it was the narrow way that Big Tech defined what it meant to be a useful, productive, successful individual. Faced with the opportunity to redefine what those things meant to me, I found it hard to push the Big Tech definitions out.

Adjusting to life after Big Tech takes time

I never found a silver bullet for the challenges of transitioning out of Big Tech, but two years on, I’ve made significant progress.

One of my biggest discoveries was the importance of structure in the transition. I create that structure with what I call an “anchor” — an activity that creates a rhythm, even though it might not take up a lot of time.

It’s probably not hitting the gym, reading a lot, or spending time with the kids. Those things are wonderful. But I think the best anchors are work-like. Someone’s expecting you to show up and do something, and you’re excited about doing it.

You might find one in learning a new skill, volunteering your time, or joining a group in your community. As long as it’s a structured obligation that brings you joy, it’ll do the job.

I found my anchor in a love of teaching. I’m a lecturer in leadership, social psychology, and UX at the School of Information at UC Berkeley.

I teach just one class a semester, but I love doing it. The cadence of preparing, teaching, and meeting with students grounds me. The deep sense of satisfaction it gives me is nothing like what my former career provided, and that’s essential.

The majority of my time is spent on executive coaching, consulting, and advising — all wonderful things that I’m thrilled to do, but all fundamentally unstructured and open-ended. Without the regular cadence of teaching, I think I’d feel unmoored.

Adjusting to life after Big Tech tech takes time. The relief and a sense of freedom to build a new career might be mixed with anxiety around your hours being your own, your goals being in progress, and your calendar being empty.

This is normal, maybe even healthy. You’re going through withdrawal. If you’ve left Big Tech and feel that same anxiety I did, maybe now you can put your finger on the cause.

You’re not doing a thing wrong. A change is underway. Reprogramming deeply engrained patterns is a tough job. But I suspect that, like me, you’ll find it’s worth it.

Business Insider approached Airbnb for comment.

Read the full article here