Apple, FedEx and Oracle all got loans guaranteed by the Small Business Administration. But rules and red tape keep many banks from making SBA loans. Chris Hurn aims to change that.

By Brandon Kochkodin, Forbes Staff

Small Business Administration loans are a great deal. They are federally guaranteed, profitable for banks, and a boon to both entrepreneurs and the overall economy (some 20% of the American labor force is employed by companies with fewer than 20 employees). But bankers hate to make them: There are 9,000 federally insured banks and credit unions in the U.S., yet only 1,452 of them made any 7(a) loans, as they are known in the jargon, in 2024. The long-term trend is bad too. Ignoring a spike during the pandemic, the overall number of SBA lenders is down 9% from 2017.

What’s going on? To hear small banks tell it, one big reason they don’t make 7(a) loans is the expertise and staff needed to navigate–and document compliance with– SBA rules. Mess up that complicated paperwork and both the bank and borrower can suffer delays or even put the SBA guarantee at risk.

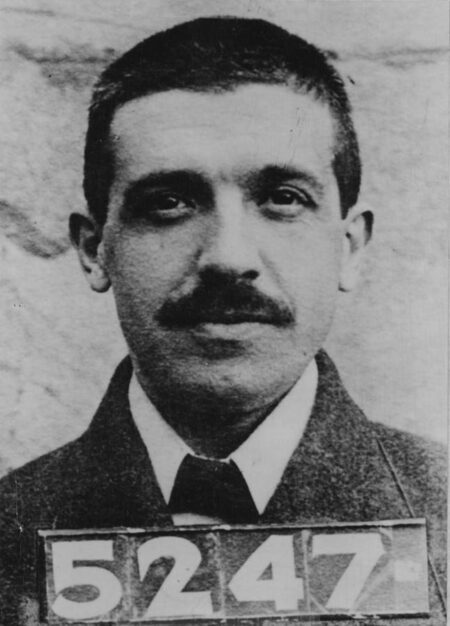

Enter Chris Hurn, 52, a big name in small business lending. He’s betting that small banks want back in on the SBA guarantee, so long as someone else handles the red tape. In January, he launched Phoenix Lender Services, a 40-person team that bills itself as a full service shop that will handle underwriting, servicing, and liquidations, so community lenders can offer SBA loans without building an entire back office or risking a ruinous mistake.

Hurn, who now operates out of Winter Park, Florida, first got involved in SBA lending in the 1990s, when he started his business career at the old GE Capital. In 2015, he founded Fountainhead Commercial Capital, a non-bank lender, which made more than $28 billion in small business loans, most of them SBA guaranteed.

Fountainhead has been winding down and Hurn has essentially moved his lending team and (after a competitive bidding process) all of its remaining $200 million SBA 7(a) loan portfolio to Phoenix, which was formed as a subsidiary of Community Bankshares, Inc., a small bank holding company in LaGrange, Georgia. Hurn joined Community Bankshares last April and became its second-largest shareholder in November.

Hurn is certainly an enthusiastic salesman for SBA loans. “You know how many companies in America had an SBA loan at one point?” he asks rhetorically. “Apple, FedEx, Oracle, Outback, you just go down the list.”

But these days, he complains, small businesses that could benefit from SBA loans can’t necessarily get them from the community banks they normally do business with. While a few big banks stepped up their SBA lending during Covid (they were heavily involved in distributing hundreds of billions in Paycheck Protection Program forgivable loans), they still punch below their weight when it comes to SBA lending. “They don’t want to sully themselves with a small business owner,” Hurn sniffs. JPMorganChase, the nation’s largest bank, was only the sixth largest SBA 7(a) lender last year.

The SBA’s 7(a) program was created back in 1953 along with the agency itself. Currently, it guarantees up to 75% of $5 million in loans to an entrepreneur to build or buy a business. (Moreover, thanks to a recent SBA rule reinterpretation, an entrepreneur can now borrow up to $5 million for each industry sector he enters; previously, the limit was $5 million per borrower.)

The idea is that with the guarantee, banks can make loans that aren’t fully collateralized–meaning they can lend on projected cash flow, giving more entrepreneurs a chance to get the funds they need to grow and succeed. Repayment terms can stretch up to 25 years, whereas conventional small business bank loans typically max out at 10 years. Last year, 70,242 loans worth $31.1 billion were approved under the 7(a) program.

Among the attractions for lenders: They can sell the guaranteed portion of a 7(a) loan on the secondary market at a premium (currently between 8% and 12% above face value), netting significant immediate income, while retaining interest payments from the unguaranteed portion and servicing fees for the whole loan. (Phoenix will help facilitate these sales, but the SBA requires that premiums go entirely to the originating bank–not to Phoenix, Hurn notes.)

By Hurn’s estimate, it would cost a bank between $1.5 million and $2 million to get into SBA lending, with much of that going toward hiring 10 to 12 people, including originators, underwriters, and back-office staff. To make it all worthwhile, says Hurn, a lender needs to extend about $25 million a year in SBA financing—something fewer than 200 lenders, or under 15% of those who participated in the 7(a) program in 2024 did, according to the SBA’s lender report. (This isn’t just Hurn talking his book– in the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation’s 2024 Small Business Lending Survey, nearly half of small banks cited a lack of expertise and staff as why they steer clear of SBA programs.)

Hurn’s pitch to lenders is simple: Outsource SBA loan servicing and get instant expertise without all the overhead. Phoenix’s fees vary depending on how much servicing a bank wants, but typically range from 1% to 3% of the loan amount, Hurn says.

It’s notable that Hurn doesn’t consider the SBA requirements excessive, given that the government’s money is on the line. “It’s just easier to blame the faceless bureaucracy of the SBA, to treat them as a scapegoat,” he says. But because of the hassle, he observes, many banks only turn to the SBA program when a customer doesn’t qualify for conventional financing, whereas he believes an SBA loan should be the first stop, not the fallback, for many borrowers. The red tape actually works in his favor, reducing competition. “It’s shrunk the marketplace of experienced SBA lenders,’’ he acknowledges.

Even those most skeptical of the government tend to support SBA loan guarantees. For example, Project 2025, the document which seems to have foreshadowed many of President Trump’s moves, suggested that the 7(a) loan guarantee limit be increased to $50 million for advanced manufacturing businesses, even as it called for the the elimination of the SBA’s inclusivity efforts and a reevaluation of its role in making direct disaster loans.

Lender service organizations like Phoenix have been around for more than 30 years, notes Bob Coleman, the founder and editor of an eponymous trade publication for small business bankers and lenders. “Phoenix isn’t the first concept, there are a lot of different entities out there,” he says. “There are some very good ones out there as well as some not so good ones.”

Coleman is, however, particularly impressed with the team Hurn has put together. “I’d say the strength of Phoenix is the talent that Chris has surrounded himself with and brought from other lenders,” he says. “They’re all pros.” Backing that statement up, Coleman points out that the SBA apparently signed off on the sale of Fountainhead’s loans to Community Bankshares, something the agency wouldn’t have agreed to if it had issues with Hurn.

As a part of a bank holding company, the Phoenix team will also be generating loans for its sister bank, Community Bank & Trust, with $176 million in assets as of October 2024.

Small business has been a part of Hurn’s world for as long as he can remember. He was raised in Peoria, Illinois, by a single mother who hustled to make ends meet. She made and sold 40 kinds of candy at local fairs and festivals, turning their kitchen and basement into a makeshift factory. Her best-seller? Chocolate suckers shaped like the Playboy bunny. “We broke every health code imaginable,” Hurn jokes. The candy business left a lasting impression. Hurn learned the basics of marketing, operations, and what it takes to run a small business—something he calls “as American as it gets.” (Talk about American, Hurn played baseball and his childhood double-play partner was future Hall of Famer Jim Thome.)

After earning his degree from Loyola University in Chicago, Hurn got a masters in government administration and finance at the University of Pennsylvania, then spent a year at Georgetown Law before concluding it wasn’t his speed.

He landed at GE Capital, which back then (in 1997) was one of the biggest non-bank lenders in the country—and a top five SBA lender. That’s where Hurn got a firsthand look at how small business lending can sour. He recalls a general contractor in Atlanta who declared bankruptcy, triggering a chain reaction. GE Capital, burned by the loss, decided to stop lending to anyone in the trades. For a lender like GE Capital—which, like much of GE, was a training ground for future industry leaders—it was easier to pull back than risk getting burned again. That once-bitten-twice-shy experience would reverberate through the lending community as the scions of GE Capital spread out across the industry.

In 2002, Hurn cofounded and became CEO of Mercantile Capital Corporation, which specialized in SBA 504 loans (those are for buying real estate and equipment with long-term, fixed-rate financing). Mercantile helped finance more than $500 million in projects for small businesses before he sold it to a bank in 2010.

Hurn himself has dabbled in small business, buying an upscale men’s barber shop (with flat screen TVs, still a novelty back in 2008). He’s out of that now but is a minority owner in two soccer clubs, including Ipswich Town of the English Premier League. He was part of the American investor group that bought the club for £30 million in 2021; it’s now valued at more than £250 million.

In case you were wondering, Hurn himself has never taken out an SBA loan.

MORE FROM FORBES

Read the full article here