Energy independence has been a focus President Donald Trump’s second term in office. He has gone so far as to declare a National Energy Emergency. However, while promises of deregulation and the removal of export controls were initially greeted with enthusiasm, that optimism has since tempered into cautious pragmatism. Increasing production to drive prices lower may be good for inflation data, but oil and gas companies must operate above their breakeven price to maintain profitability. Said simply, satisfying campaign promises to consumers and making it easy for oil executives to do business are objectives that aren’t easily reconciled.

The Crossroads of Energy Policy and Business

One of the defining features of Trump’s energy policy is his commitment to energy dominance and decreasing our country’s reliance on foreign energy means we need to drill baby drill! This means increasing domestic oil and gas production, rolling back regulations that were perceived to inhibit fossil fuel extraction, and positioning the U.S. as a global energy powerhouse. Key to this strategy is the promotion of the U.S. shale industry, which has revolutionized domestic energy production over the past decade. The U.S. has surpassed Russia and Saudi Arabia to become the world’s largest producer of crude oil. But further increasing energy production may be a tough pill for oil executives to swallow. An increase in production puts pressure on prices and puts pressure on existing oil infrastructure. Drilling a new shale well is not a huge cost in and of itself, but increasing production above current record levels may necessitate spending on transportation or storage systems – programs that require more up front investment with a longer payback timeline.

Perhaps more important, not everything the administration has done so far has actually streamlined the process for oil companies to invest and drill. While President Trump has been vocal about encouraging energy policy, the Department of Government Efficiency’s cuts to the Bureau of Land Management and Energy Department has slowed the process for attaining export licenses and permits.

Furthermore, Trump’s broader economic policies – specifically his tariffs on steel and aluminum – have had a significant impact on U.S. oil and natural gas production. These tariffs directly increase costs for producers, particularly in the construction of drilling rigs and pipelines. Steel pipe prices in particular are a significant line item in the construction of new oil and gas wells. Uncertainty around steel pricing invariably pushes the cost of production higher as it makes it more difficult for the engineering teams to accurately estimate future expenses. This in turn slows down expansion plans, especially in the offshore drilling sector, which requires heavy infrastructure investment.

Tariff uncertainty is also affecting the downstream U.S. oil and gas industry, particularly companies reliant on specific imported oil types. Decades of investment in transportation infrastructure and refineries designed for certain crude grades make continued imports essential, despite rising domestic production. As a result, much of the oil drilled in the U.S. is exported, while a significant portion of refined oil is imported.

Canada plays a crucial role in this dynamic, supplying 98% of its crude exports to the U.S., accounting for nearly 60% of U.S. oil imports. Alberta’s oil sands hold one of the world’s largest reserves, and their thick, heavy crude is a key input for Midwest refineries. Any tariffs on Canadian oil would likely be passed on to U.S. consumers, as these refineries do not have many other potential suppliers.

Energizing The US Shale Revolution

Horizontal drilling technologies have unlocked previously inaccessible reserves of oil and natural gas, particularly in the Permian Basin, which alone accounts for over four million barrels per day of oil production. This surge in production has made the US the largest producer globally. Perhaps more important, U.S. shale producers can move very quickly and are highly responsive to price signals compared to traditional drillers. When global oil prices rise, U.S. shale producers quickly ramp up production, often outpacing the ability of traditional oil exporters like OPEC member countries to adjust their output.

This toggling of production is possible because of how shale oil is extracted. Traditional wells take longer to develop but can produce oil for decades. In contrast, shale wells can be drilled in just a few weeks and typically last only two to three years, with most production occurring in the first 12 to 18 months.

This shorter lifecycle allows shale producers to respond more quickly to market volatility and policy shifts, optimizing capital allocation. However, shale production is relatively expensive, with high production costs and breakeven prices between $40 and $50 per barrel. Because of its price sensitivity and short investment horizon, shale acts as a global marginal producer. When oil prices rise, shale wells can be rapidly deployed; when prices fall, investments slow, and production declines, helping to stabilize supply and prices.

Disciplined capital allocation has become a primary feature of the oil industry since the oil boom and bust in 2015. High efficiency wells have allowed drillers to produce more with less. As of March 21, there were only 486 active rigs in the US, a significant decline from the 1,500-plus rigs in 2015. Technological innovation has pushed up production, minimized operational costs, and allowed drillers to be careful with their capital deployment during times of uncertainty.

The Natural Gas Transport Dilemma

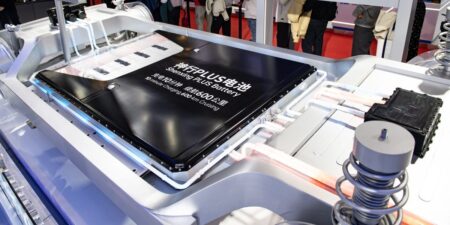

Less discussed than the push to drill for oil is the potential for the US to become a dominant player in the global trade of Liquified Natural Gas (LNG.) Natural gas is often closely tied to oil drilling as both resources are commonly found together in hydrocarbon reservoirs. Natural gas has historically been harder to transport and a lower margin good. However, innovation in cooling technology has made the liquification and transportation of natural gas more viable. Liquification reduces its volume by about 600 times allowing for more efficient storage and transport. LNG can be shipped via tankers or distributed through pipelines for use in power plants, industrial manufacturing, and even transportation.

The United States is the world’s largest LNG exporter, ahead of Qatar and Australia. And the world wants what we have to sell. While the focus for power in most developed countries has been on renewables, there is still insatiable demand for new power capacity beyond what renewables can deliver. Natural gas has the opportunity to compete with coal, diesel, and other inefficient power sources across the globe, delivering cleaner and cheaper power. While not necessarily a clean form of energy, natural gas emits far less greenhouse gases when burned compared to oil and coal and is helping to bridge the gap in the transition towards cleaner energy. according to the International Energy Agency, coal consumption reached a record high in 2024 at 8.77 billion tons!

The primary constraint on LNG today is transportation capacity. While liquefaction plants are under construction at U.S. ports, these projects take time to complete. Currently, natural gas is oversupplied. In 2024, prices at the Waha Hub in West Texas even turned negative due to limited takeaway capacity, forcing producers to pay to have their gas transported away.

New natural gas production is unlikely to expand significantly until more liquefaction infrastructure is completed and takeaway capacity improves.

Macro Factors Affecting Energy Production

While energy companies are balancing tariffs and supply/demand dynamics, there’s also the macroeconomic variable like inflation and interest rate levels they need to keep in mind. While inflation has been inching its way back down to the Fed’s 2% target, rising costs for labor, materials, and equipment mean oil and gas producers face higher operational costs. The impact of inflation has been particularly evident in the upstream sector, where rising costs for drilling rigs and labor have made it more difficult to maintain production levels without significant increases in oil prices.

As it relates to interest rates, throughout much of Trump’s first term, low interest rates made borrowing cheaper, allowing oil and gas companies to finance new exploration and production projects. Now, the shift towards a more normalized rate environment has had a significant impact on shale oil producers, many of whom rely on debt to fund their capital-intensive operations. These companies now face higher borrowing costs than before, which may result in a slowdown in drilling activities.

Investing in Energy Independence

The upstream sector, which focuses on oil and gas extraction, remains the most volatile but also offers significant potential during periods of high oil prices. The rise in interest rates and inflation could dampen the growth prospects of shale oil producers, particularly smaller companies that are highly sensitive to borrowing costs. However, large-cap shale producers like ConocoPhillips or EOG Resources are well-positioned to weather these challenges.

Investing midstream involves the transportation, storage, and distribution of oil and gas, and tends to be more insulated from commodity price fluctuations. Many midstream companies like Kinder Morgan (KMI) or Enterprise Products Partners (EPD) operate under long-term pricing contracts that can provide more stability in volatile markets.

On the other hand, refineries downstream regularly see big swings in their profitability. Large-scale refiners like Marathon Petroleum (MPC) and Phillips 66 (PSX), and independent refiners like Valero Energy (VLO) dominate space, but the capital intensive and cyclical nature of the business is difficult to forecast for executives and investors alike. In fact, no entirely new large-scale refineries have been built in the US since the 70’s.

Wrapping it Up

The path to U.S. energy dominance involves balancing a variety of economic, geopolitical, and technological factors. While President Trump’s energy policy initially spurred optimism in the oil and gas sector, the realities of production costs, environmental regulations, and international trade uncertainty continue to create challenges for producers. The U.S. shale revolution, while impressive, has highlighted the volatility of the market, with factors such as fluctuating global demand and negative pricing episodes underscoring the difficulties in sustaining long-term growth. Despite these challenges, there are still opportunities for growth, especially for larger, well-capitalized producers who can navigate these complexities. Ultimately, achieving energy independence requires a delicate balancing act, and the ongoing adjustments made by both policymakers and industry leaders will shape the future of U.S. energy for years to come.

Read the full article here