As markets eagerly await Friday’s release of the latest Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE) Price Index figure, the US Federal Reserve’s (Fed) preferred indicator for gauging inflation, investors know that this report will weigh heavily in September’s interest rate decision.

But why is this figure, less well known than the Consumer Price Index (CPI), so central to US monetary policy?

PCE vs CPI: Two measures, two rationales

For most Americans, and even international observers, inflation is measured by the CPI.

The CPI, published by the Bureau of Labor Statistics, measures changes in the prices of a fixed basket of goods and services that represent urban household spending.

It’s the most widely publicized inflation measure, and the one that hits the headlines when talking about the price of rent, food or gasoline.

The PCE, on the other hand, is less well known to the general public, but is preferred by the Fed.

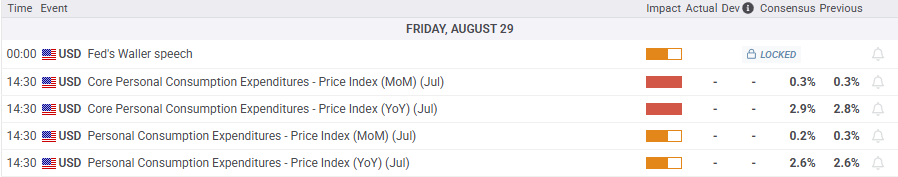

Personal Consumption Expenditures. Source: FXStreet

Calculated by the Bureau of Economic Analysis, it covers a broader field. Not only expenses paid directly by households, but also those paid on their behalf, such as healthcare financed by employers or public programs.

Its more flexible methodology better incorporates changes in consumer behavior. For example, switching from beef to chicken if red meat prices soar. In other words, the PCE more accurately reflects the reality of American consumption.

Finally, the PCE is adjusted to consumer habits or changes more frequently and draws on a wider range of administrative sources, making it a more accurate and stable barometer than the CPI.

It is for these reasons that, since the early 2000s, the Fed has adopted it as its main tool for assessing whether or not inflation is close to its 2% target.

A decisive indicator for the September meeting

Friday’s report is of particular importance. It will be the last PCE inflation release before the September 16-17 Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) meeting.

The analysts’ consensus expects headline PCE to have risen by 2.6% year-on-year in July, a pace still above the Fed’s target.

More worryingly, the core PCE, which excludes the more volatile food and energy prices, is expected to have accelerated to 2.9%, after 2.8% in June.

Economic calendar. Source: FXStreet.

These figures complicate the Fed’s task. On the one hand, keeping key interest rates high, currently in the 4.25% to 4.5% range, would make it possible to contain inflationary pressures fuelled in particular by the US President Donald Trump administration’s tariff hikes.

On the other hand, the marked slowdown in the labor market argues in favor of easing policy to support activity.

Powell between inflation and employment

During his speech at the Jackson Hole symposium, Fed Chair Jerome Powell underlined this dilemma: “The labor market appears to be in equilibrium, but it is a curious equilibrium, marked by a joint slowdown in the supply and demand for workers”, he declared.

Job creation has slowed sharply to an average of just 35,000 new jobs per month over the past three months, according to the Nonfarm Payrolls report, while statistical revisions have removed hundreds of thousands of previously announced jobs.

This context is prompting the Fed to reconsider the weighting of its dual mandate: price stability and full employment.

After a long-standing focus on inflation, Powell hinted that employment risks could now weigh more heavily on the central bank’s decisions.

“If these risks materialize, they can do so quickly, in the form of a sharp rise in layoffs and unemployment,” he warned.

A risky bet for the markets

Financial markets are betting heavily on a rate cut as early as September, which would give the economy some breathing space.

However, too rapid monetary policy easing could rekindle inflation at a time when tariffs continue to push up the prices of consumer goods.

In other words, Friday’s PCE report could well tip the balance: confirm that inflation remains too high to justify monetary easing, or, on the contrary, allow the Fed to begin a cycle of interest rate cuts.

Either way, the equation is more complex than ever. Chair Powell will have to arbitrate between persistent inflation and an increasingly fragile labor market.

Read the full article here