I’ve long considered myself a first-generation American. Both of my parents were born in Germany and emigrated to the US in the 1960s. We lived in Virginia, but I grew up bilingual, speaking English at school and German at home.

My childhood was full of German traditions. Every year, my grandmother would visit from Berlin to take care of us during our summer vacation. She didn’t speak English, so we spoke German all the time. We also visited my grandparents in Germany two or three times a year. Berlin was more than a city to me. It was a second home, filled with familiar smells, voices, and generations of family.

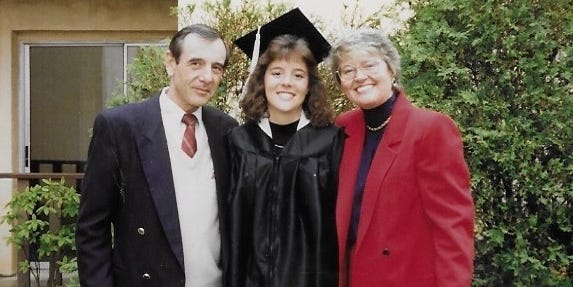

But when my father and grandmother died in 1991, two weeks apart, everything changed. I was 24. Their deaths marked a turning point not just emotionally, but culturally. My use of the language faded. The trips stopped. Germany became a memory, vivid but distant. For decades, I assumed that part of me had quietly ended with them.

A podcast conversation made me question what I really knew

Lately, through my podcast, “Living Ageless and Bold,” I’ve had more guests talking about heritage, ancestry, and identity. Their stories sparked something in me — a curiosity I hadn’t felt in years.

One day, I wondered, “Could I get dual citizenship?” I had no idea how the process worked. I assumed it would be complicated or even impossible, but I decided to do some research.

Through the Freedom of Information Act, I requested my father’s naturalization records. When the documents arrived, one line jumped off the page: He became a US citizen on July 13, 1967.

I was born January 26, 1967 — six months earlier.

“You’re already German!”

I did some research and learned that, according to German law, if a child is born before a parent gives up their citizenship, the child retains German nationality by default. I wasn’t “eligible” for dual citizenship because I was, and always had been, a German citizen.

I visited the German Embassy in Washington, D.C., to confirm everything and apply for a legal name change to match my married name, so I could then apply for a passport.

The woman behind the counter looked at my documents, smiled, and said, “You’re already German.”

She told me it was rare, as most people apply through the descent process. I didn’t need approval. I simply needed documentation. It was already mine.

The legacy didn’t end; it waited

As I walked out of the embassy, something unexpected happened: I started crying. Not because I was now eligible for a passport, but because I felt my father again. After all these years, it felt like he had reached across time to remind me that he, and everything he had given me, was still a part of my life.

Then came another surprise: Because I am a German citizen, my children are too, and theirs will be as well. They never met my father. They never heard his voice. But now, they carry his legacy forward.

Now, they are linked to that side of the family in a way that goes beyond photo albums and stories. They are part of a lineage I thought had been cut off in 1991. Instead, it continues.

I found a piece of myself I didn’t know was missing

This wasn’t just about citizenship or paperwork. It was about identity — the kind you don’t always realize you’ve misplaced until you find it again. For most of my adult life, I thought I was an American with a German background. Now I know I’m also a German with an American life.

It’s easy to believe our pasts are fixed, especially when a parent dies. But sometimes, buried in a file or hidden in a date, is something that reawakens the past and hands it back to you, not as a memory, but as a living, legal truth.

My dad died when I was 24. This year, at 58, he gave me one last gift: a way to reconnect with him, with where I came from, and with a part of myself I never expected to find again. It turns out the most meaningful legacies aren’t always passed down; sometimes, we have to go looking for them.

Read the full article here